This post is a response to a question posed in its complete format: “How did the internet reach a point of legitimately being something that no one knows how to shut off in the event of an emergency? Do you think there’s any reason it should have a way of being done?

I’m struggling to think what sort of emergency could possibly warrant shutting off a global environment of interconnected devices while I’m watching the run of Terminator movies.

If Skynet were to become a global threat, then shutting down the entire globe of interconnected machines could not occur quickly enough to defuse such a fictional threat.

Local isolation areas could occur through coordination with service providers, which might be sufficient to limit Skynet’s reach, but doubtfully, because that imaginary AI with a vengeance streak would not make itself so obviously a threat before it’s too late to do anything about it.

Next, a more realistic threat could be a sophisticated virus that propagates throughout the Internet and is likely undetected until triggered into action. Any coordinated shutdown of internet trunks and backbones would still not stop it.

All efforts to mitigate the effects of such a virus would have to be applied locally to billions of connected devices.

It is likely advantageous to maintain internet connectivity to deliver an antiviral payload.

Again… I’m at a loss to identify what possible threat could warrant shutting down or blocking all connectivity between devices.

If such a feature were possible, it would constitute a more significant threat that bad actors could exploit.

Shutting down significant connections could disrupt vast swaths of many economies, making nations vulnerable to extortion.

In this light, such a feature seems more of a threat than any imaginary one, justifying exposing global connectivity to such a weakness.

The primary strength of the Internet is its vast array of redundancies that we will need to rely on to save our asses with increasing climate emergencies ahead.

Your question is born from a mindset where you imagine a coordinated rollout of connecting technology applied uniformly to billions of devices.

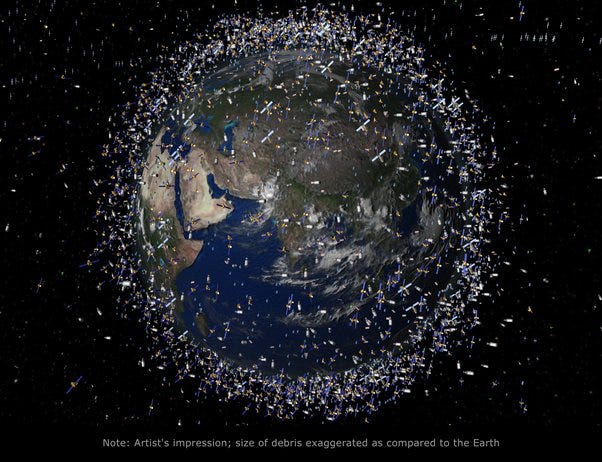

That’s not how the Internet came about and grew into a state of global coverage created by an array of trunk lines floating in the ocean and satellites in orbit.

The Internet began small (like everything massive typically does) by hardwiring two computers to each other and developing protocols that permit information exchange.

From there, it grew into supporting military and scientific needs for coordinated information-sharing. From there, tech nerds at the forefront of computer technology shared information on virtual public bulletin boards.

From there and at the beginning of the 1990s, Timothy Berners-Lee wrote protocols for assigning unique identifiers to devices that would allow information to be directed to intended devices in a chaotic system of signal transmissions. He also invented a “Hyper Text Markup Language” that converted computer code into “human-readable pages.”

He is widely known as the “Father of the Internet.”

The Internet grew by quantum leaps year by year as businesses, schools, and homes adopted computers that could connect.

Private companies launched satellites and installed trunk lines while laying down millions of miles worth of cable into a spiderweb of interconnectivity — hence the term “World Wide Web” — the “www” following “http” (hypertext transfer protocol).

While posting a message on my Facebook page asking Mark Zuckerberg to improve blocking on Facebook, I looked up the total number of users, and its numbers were 2.9 billion people on Facebook alone.

All of this has been as far from a coordinated strategy of development as could be the case.

There has never been a perceived need to hamper the primary strength of an always-on internet connection. When failures occur on a localized basis, that entire affected area is in disarray from the disruption.

There exists no means to quickly shut down such a chaotic arrangement of interconnected devices because that’s antithetical to the purpose of the Internet in the first place. At most, an EMP pulse could disrupt a localized area quickly, but that’s about the extent to which a rapid shutdown is possible.

UPDATE:

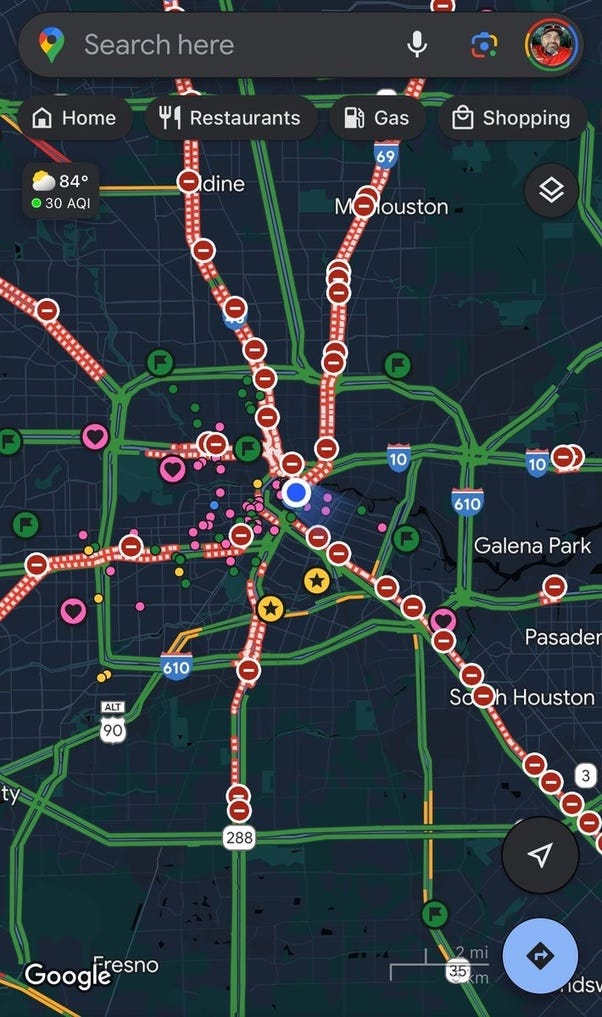

As it turns out, one of the benefits of redundancy is when a privatized corporation tasked with the responsibility of helping citizens survive and navigate an environmental emergency fails to live up to its commitment, another corporation with an app to sell burgers ironically fills in the life-saving service gap to assist people and ostensibly fill their bellies with burgers and fries.