This post is a response to a question posed in its complete format: “Why are people so reluctant to call out “artists” like Mark Rothko for the sheer worthlessness of his ‘art’?”

“Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.”

This is a flawed presumption because people have no problem expressing their views on the arts they encounter.

Of all the vocations humans indulge in, none are exposed to as often to emotionally charged criticisms as the arts, much like how this question seeks validation.

The question is an admission of failing to understand numerous aspects they reject on a visceral level, while depriving oneself of an honest intellectual process of critical analysis.

This is a question ruled by pure bias in the same way all forms of intellectually stunted bigotries are concocted.

This question also reveals a mindset incapable of appreciating Gestalt and is more enamoured by puerile rather than reflective experiences.

These paintings cannot be judged by their reproductions in a book or onscreen.

They must be experienced in person to apprehend their meaning.

As much as the question seeks to disparage and devalue the valid contribution of a life dedicated to the furtherance of one’s craft and vision — such that their work will be remembered for centuries, in contrast to this puerile critic who will be a long-forgotten example of a juvenile apprehension of what they are intimidated by.

The fact is that your subjective tastes in art do not serve as a universal metric of value. No single individual has that power.

Value is determined by a complex dynamic involving institutions and people with depths of historical awareness that far surpass the childish apprehension of what this question celebrates as a mindset.

One the first bits of wisdom I encountered as an Art student is as follows: “When people say, ‘I don’t know much about art, but I know what I like.’ they are actually saying, ‘I don’t know much about art, but I like what I know.’”

This question is an admission of being out of your depth, and you’re freaking out about drowning in being touched by the ineffable. You can’t handle letting yourself go and float freely within the infinite.

This question screams “shallow-thinking and egotistical control freak” to me.

I’m sorry you are struggling with his work. Your question, however, indicates you need to engage with it until you can experience the revelation that will allow you to transcend your intuitively recognized intellectual limitations.

Your visceral reaction to his work is your intuition telling you to focus on something you have been avoiding and repressing within your psyche.

Take these words however you like but try not to ignore how easy it is to call out horseshit when one sees it.

No one has been “reluctant to call him out.” That’s nonsense because no other vocation is nearly as “called out” as an artist’s.

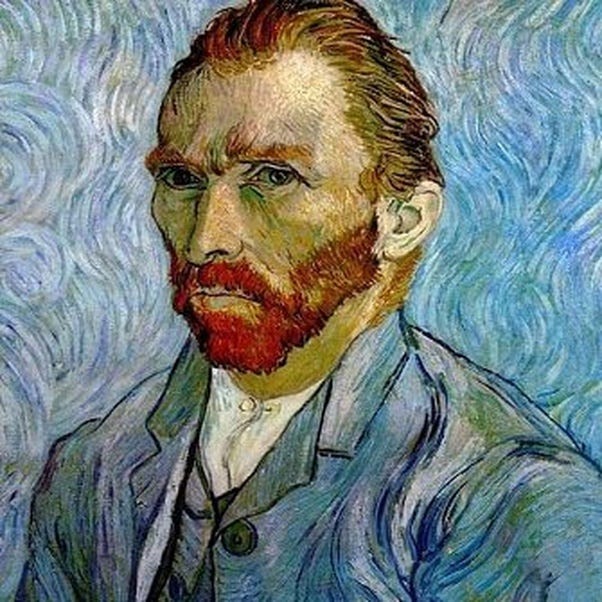

Mark Rothko’s work has not gone without intense criticism. However, it persists, and that persistence determines its value in the same way all artists throughout history have been rejected by their era. Countless artists throughout history have engendered emotional rejections to their work like yours, while a famous one most know of is Vincent Van Gogh.