This post is a response to a question initially posed on Quora, and can also be accessed via “https://divineatheists.quora.com/How-do-atheists-view-the-concept-of-being-born-again-60“

I remember someone I once trusted approaching me for relationship advice.

I don’t remember the specific complaints registered against him by his then-recent ex, but I remember how he tried to convince her that he had changed overnight.

The next day after she ended her relationship, he returned to her and claimed he had changed.

After relating that to me, I tried to explain to him that’s not how change works. One doesn’t change oneself like they change their clothes, most certainly not overnight.

That wasn’t my best approach to helping him overcome his anxiety. He outright rejected what I tried to get him to understand. I believe that was the last conversation he and I ever had.

However, His attitude toward change stuck with me as I struggled to understand that thinking. I thought of it as chillingly superficial and worse as it appears to be an attitude which fits within the mindset that justifies telling people what they want to hear.

Everything about how a certain mindset perceives the world around them is based entirely on optics, and their behaviours are mere performances designed to elicit desired responses from their audience.

It left me feeling cold, and I’ve learned to understand how severe a red flag that is. I wish I hadn’t been such a slow learner in this regard because I could have saved myself a world of hurt if I had fully considered the implications of that behaviour then.

At any rate, the notion of undergoing a transformative experience had always intrigued me as I deliberately sought paths and methodologies for transcending limiting ways of being. From a very young age, I was aware that I was conditioned into being what I conceptually rejected but required something tangible to transform my desire for change into actual change.

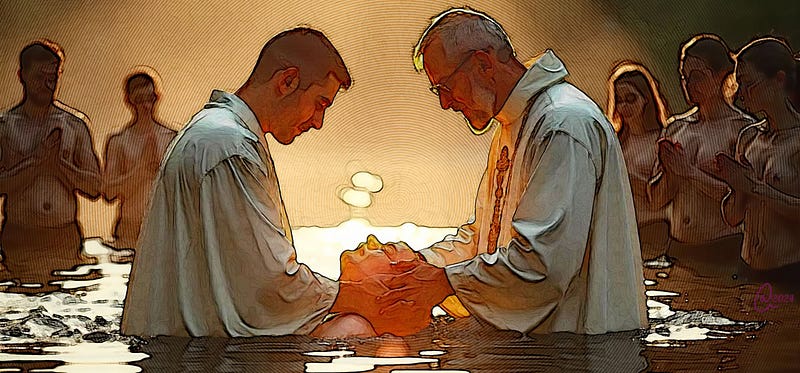

Symbolically, the notion of being “reborn” is a ritualized performance in which people present themselves as if they had changed from committing to a belief system and being “remade” by that commitment itself.

People who have undergone such a ritual sincerely think they have transformed into a better version of themselves. Their exclamations, however, have more often been expressions of hopeful anticipation rather than observable reality.

Their subsequent behaviours and fundamental attitudes remain the same. From an outsider’s perspective, the only change visible was the compass setting they prioritized.

Although some stick with their new compass setting over the long haul, many returned to being who they always were while dismissing a temporary compass setting as one they outgrew and was no longer relevant to them.

Some remained within their faith but regarded it with their “old eyes” and treated their entire relationship with their beliefs and community as a game of optics. Others moved on as they acknowledged their experience as helpful but not enough to commit to it for a lifetime. I found this latter group more authentic in their journey of discovery. The clarity of direction or need they expressed as they described their choices through fogs of confusion they struggled to dispel always made them feel more human to me. In contrast, I found those who appeared to skim through emotional turmoil somewhat confusing. I didn’t know how to interpret their responses to emotional struggles. I must have envied them as I could never respond to my own in similar ways and often wished I could have. It seemed to make life easier for them.

These “performers at life” always made me feel cold, though, and it’s taken me a long time to understand why.

Understanding how a proportion of our population lives through a shallow lens may be conceptually easy to grasp superficially, but that’s not a satisfying apprehension of the phenomenon. One inevitably finds oneself mystified by its manifestations while wondering why they feel put off in ways they don’t quite understand. It can be a harrowing journey to fully grasp the implications of such a life on a visceral level for those whose feelings run deep.

Another example was an individual who had been married for about six years and who I had gotten to know as a close couple who seemingly shared everything. Conversations with either always involved extolling the virtues of the other and never was an unkind or critical word shared. I thought they were a remarkable example of a successful couple until the husband informed me they were getting divorced.

Their separation appeared as if life sped forward at super-speed for them because it all took place within a couple of weeks — from agreement to the formalized documentation of divorce. There was no emotional turmoil I could detect in the husband, as the ex-wife had already left, and I had no means of gauging her condition. In his case, however, I was more shocked at his ability to move on than I was at their separation.

For him, it was as if nothing of note had happened in his life. I couldn’t fathom that, particularly after having endured my periods of extended angst over far shorter and more superficial commitments. I remember envying his ability to rebound from what would have been at least a year or two of turmoil for me.

I didn’t realize until later that his personality was characterized by subtle paranoia and mistrust toward others on mostly innocuous levels. I first noticed that aspect of his character after he described a business venture I found myself intrigued by and expressed how much I liked it. His response became immediately cold and protective of it. He clarified that I had no place in his venture even though I had not expressed such desire or intent.

I remember switching the conversation at that point and inquiring about his ex-wife, and I was curious to know if she was doing well. His response was mainly dismissive, but he let the cat out of the bag by indicating that the reason for their divorce was his unfaithfulness.

The ability to move on quickly from a profoundly emotional experience had often been a source of admiration for me. That was before I understood the costs of such a state of being — to both themselves and those they inevitably victimize.

I don’t think he was ever capable of connecting deeply with anyone, and I didn’t understand, even then, how profound that was. I knew it was essential for me, and I accepted how that might not be for others. I didn’t think of it as a toxic dysfunctionality — even though I should have known better after having experienced it with many others so often throughout my life.

From a ritualistic perspective, there can be some benefit to undergoing a formalized process that symbolically represents change and, more importantly, a desire for change. However, it’s all done for optics more than acknowledging the necessity of change and its role in one’s personal growth.

I always have felt this way, but I never understood how that attitude itself, on my behalf, was present even as a child when I underwent my first confession. It wasn’t conducted in a booth but in an empty classroom on a chair across from the minister. We were in full view of each other without obstruction, and he asked me to speak.

I struggled to find words while suppressing a broad smile as I found the experience entirely superficial. After all, how could I possibly be exonerated of guilt over actions I may have taken that were considered sinful by simply uttering them to this stranger? At the age of eleven, the most egregious sin I could think of was masturbation, and I suppose that might have been why I struggled to suppress a broad smile.

Within a belief system that purports to provide adherents with pathways for growth, I can understand and support the prescriptive manner of formalizing rituals to celebrate that growth. The shortfall in converting subjective experience into an objectively procedural system is that it fails to account for individual differences. It is a process that cannot account for or mitigate abusive misuse.

Much like the reporting systems across all social media, the symbolic ritual of change is a tool that can be weaponized for personal gain. The emphasis on optics is a form of corrupt thinking which overlooks the critically ineffable in favour of supporting shallow expedience.

The concept of “being born again” is just a formalized process of stripping profundity from life in favour of optics because we do not, as a whole, value depth in a world that has industrialized human existence and reduced the human condition to the level of a disposable commodity.

We have evolved into an increasingly dehumanized existence while being led by institutions that claim to represent higher states of being. Our only hope for reclaiming our existence as human beings capable of achieving our potential is completing our transformation into a fully automated society. It will only be once we cross this threshold that human beings will be free of the superficial trappings of optics made necessary by the industrialized herding of our species. The function of symbolic optics is an inherent limit to our potential as individual beings within what we refer to as “civilized society.”

I believe the concept of “being born again” should be viewed with great suspicion and mistrust because it reflects nothing of an individual’s inner world or the foundation of their character.

It can, however, be a practical means of applying a metric for identifying differences between that standard and one’s words and deeds to triangulate a more accurate picture of one’s internal world.