This post is a response to a question posed in its complete format: “Aside from it being a moral duty, why should I contribute to society?”

As a reason to contribute to society, a “moral duty” represents a form of coercion which garners the absolute least that one will contribute. Referring to contributions made to society as a “moral duty” creates the perception that it’s like paying a tax. You do it because you have to.

That’s the best way to get the worst attitudes and the least value in contributions from people.

“Paying it forward” is a far better way to frame contributions to society because it serves as a reminder of how one has benefited from society and the contributions of others as part of a shared community.

Another context that can help to imbue the concept of contributing to society with motivational meaning is as a team. As members of a species, we are all members of the same “team” in the sense of our challenge to maintain survival. This perspective is why I chose the concept of a bucket brigade to illustrate the idea of working together to put out a fire.

Understanding the difference in perspective between one who feels they “should” versus feeling like one “can” will clarify the attitude we should be cultivating in society to encourage contributions back to society. When a person feels like they’re a valued member of a supportive community that enables their members to achieve their best potential, it cultivates an attitude of gratitude that prompts people to think positively of what they can do in return for their community.

Think of it like gift-giving during the holidays, where people go to great lengths to impress someone with a special gift they know will be meaningful to the recipient, versus the sentiment people demonstrate when put in as minimal an effort into their gift as they can get away with to meet an expectation from someone they don’t care about but feel an obligation to gift them something.

To do what one “should do” invites the minimum effort to meet a bar of expectations set by the lowest common denominator and is characterized in the best of terms as an apathetic form of disengagement from one’s community. Why give something to society when you don’t value it?

Conversely, when one feels closely connected to a community that has cultivated gratitude within their mindset, they want to give as much as they can afford to adequately express their appreciation for what they value receiving from their community.

To do what one can, rather than what one must, is to be motivated by a natural desire to contribute out of a spirit of reciprocity.

This is why the social contract is crucial to our health as a society and why community development is an essential mindset for leaders to adopt and cultivate within society. Community members who feel they belong to a larger dynamic and are valued for their contributions are engaged and self-motivated to do what they can to improve life for everyone else.

They understand and value the meaning of the words, “We are all in this together.”

This sentiment is the glue that will keep society from collapsing into chaos during the most troubling times.

This sentiment is the glue that has given humanity the grace to survive and prosper to such a degree that our short presence here will be as lasting into the future as hundreds of millions of years of a planet dominated by dinosaurs has been to date within a fraction of the time they existed.

When one feels connected enough to something, they have no problem going out of their way to contribute as much as they can afford because they believe their giving is its own reward. They derive pleasure and fulfilment from giving to their community. They will go to great lengths to contribute as much as possible to their society because giving transcends moral duty.

Some people will give to causes, for example, because they want receipts to lower their tax burden through the benefit of deductions.

Other people give to cancer research, for example, because they have been personally affected by the issue. Giving as much as they can afford is a way of coping with the issue by acknowledging a loss or a deeply impactful experience. Giving is rewarded by a cultivation of hope within oneself.

Many people volunteer their time in contributions to a cause because of the social connections they create and benefit from on an intangible level. Giving energizes one’s spirit through interpersonal interactions and cultivates the interconnectedness that defines a core need for the human condition.

In all self-motivated cases, one’s contributions are made without considering moral implications because those are justifications which devalue the experience.

In all cases, people give in greater abundance and more honestly of themselves when internally motivated by intangible and intrinsic benefits than by material and extrinsic ones.

Understanding why one would want to contribute to society out of an internally motivated reason is far more crucial to the value of one’s contributions than meeting an arbitrary degree of obligation.

Understanding how one has benefited from the efforts of those who came before us and how we are each linked in a centuries-long chain of humans collectively contributing to an aspirational future for all of humanity is how to convert an obligation into a desire.

When we are disconnected from our humanity and community as humans, we lose sight of the value of our contributions to an evolving whole.

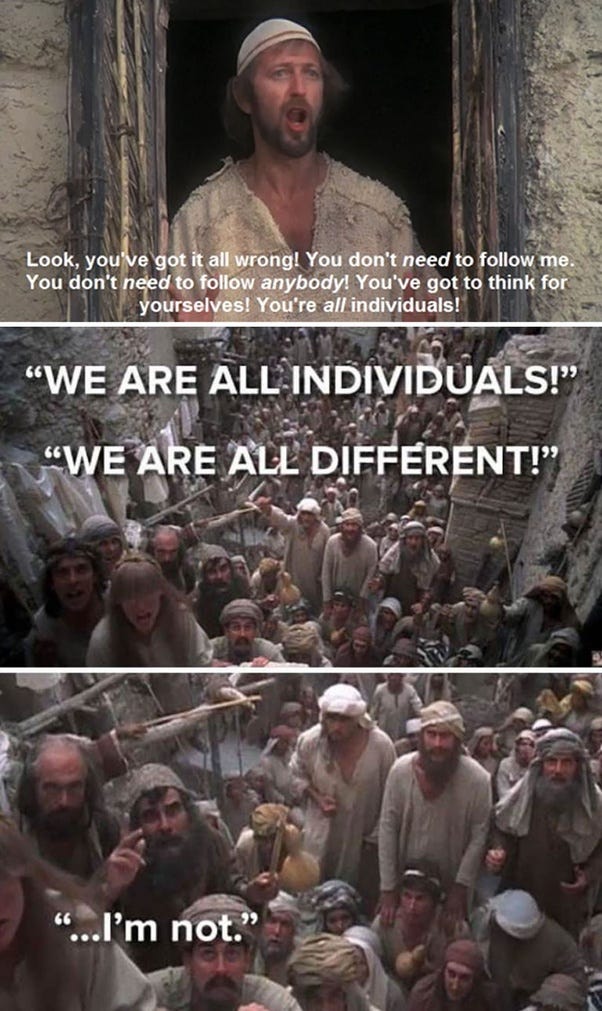

Learning to appreciate our distinctive differences between individuals and celebrating those differences while embracing the uniqueness of their contributions is how we can justify giving the best of what we can to those who will come after us and allow us to be remembered as individuals who each gave our best to make their lives better.

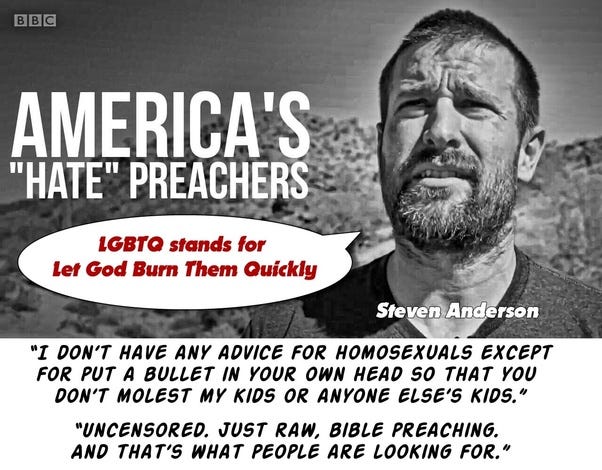

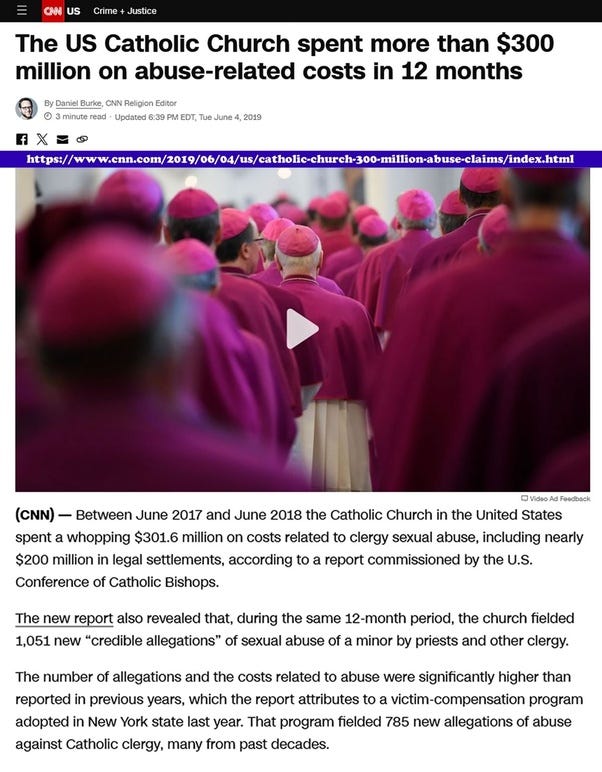

Cultivating this community spirit of belonging is how we survive our challenges, such as those we are struggling through today. Our connection to community allows us to cope with and overcome being inundated by the toxic influences of those who lack appreciation or reverence for the sacred nature of what we collectively benefit from.

Encouraging the creation of connections between us results in a superior form of morality that organically emerges in society to endure throughout our existence on this planet more successfully.

There is no valid reason why you “should” give back to society. However, without a desire to give back to society, you have lost out on one of the most valuable sentiments a human can experience, which is core to our development as healthy humans living fulfilled lives.

Bonus Question: How do you accept the fact that no one loves you?

Learn how much more important it is to love yourself and life than to be loved.

No two people or living creatures love in the same way.

Love is not about receiving but about giving.

If you want to be loved, get yourself a dog and/or a cat, or several.

If you can love what you do each day, it can sustain you enough to allow other forms of love to make their way into your life.

Good luck.