Today’s post is a slight shift in gears. Rather than the simple formula of posting an answer to a question, I’ve included a dialogue following a short answer given to a question, which, in its complete format, is, “If we died and stopped existing, how long would we have to wait to be born as a new animal? Would time fly? Would we recognize we had been dead for hundreds of years?”

The universe is at least thirteen billion years old. Do you have any awareness of anything outside your experience of life?

No, because you did not exist before existing now. You will not exist again.

When you die, you stop existing. There is no “waiting” for anything. There is no time. Death is not a timeout from life.

This finite period of existence is all there is.

Learn to appreciate it as much as possible because once it’s gone, it’s gone.

Commenter (CS): I think a lot of you are missing the point if you don’t exist the universal find a way for you to exist

AA: Nope… you are missing the point. Once you’re dead, you’re dead. Whatever it is that you think constitutes “you” is gone forever.

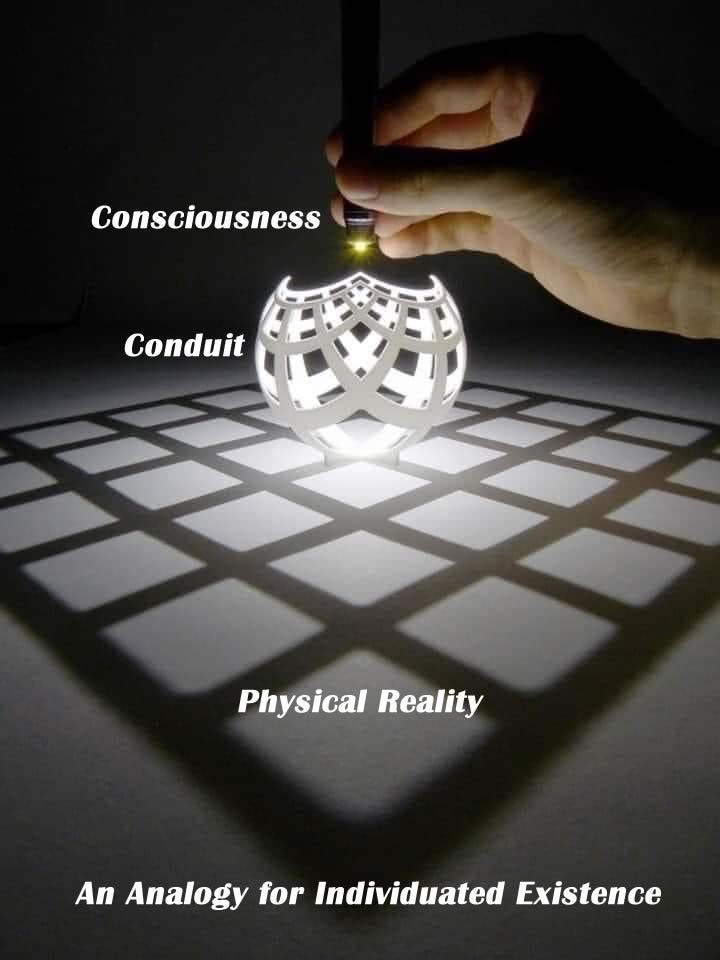

If something that you might speculate exists beyond the “you” that exists in physical reality is something which makes you “you” and that you are a part of, it is not “you”… it is something else. If something else you speculate exists beyond physical existence, the “spark” makes you you. It accomplishes that task through physical phenomena, resulting in epiphenomena known as “ego, superego, and id.

“You” are not that “eternal thing.” “You” are a temporary thing called “ego.” “You” are the flame on a match that disappears into nothing when the wood has burnt.

Accepting this truth is the broad lesson of humility all of humanity must learn to transcend this tentative existence.

Commenter (CS): I agree with you to a point we will be dead yes . but if something doesn’t exist something that exists in the future . will be atoms that once made us meaning we will live again but not as us I’m not talking about reincarnation I’m simply talking evolution atoms are the building blocks of life if we don’t exist the atoms will make us exist.

AA: No. Atoms merely form the physicality of our existence as conscious beings. If physicality is the limit of our existence as conscious beings, then that only reaffirms the argument that there is nothing more beyond this finite existence for any of us.

The religious take on existence is that we are part of something greater. Our latest investigations into the concept of consciousness indicate that something of that notion may be true. For example, “Integrated Information Theory” (IIT) posits that all of the universe’s physicality essentially is information that persists indefinitely, if not infinitely.

That means whatever constitutes a life persists long after that physical life is complete… like a library of documentaries. This begs the question of whether or not that library is accessible and accessed by something speculative.

Whatever the case may be, the fact is that the “you” which exists within this finite frame of spacetime exists only within this finite frame of spacetime. The two concepts in these two paragraphs also imply that the “you” experiencing your life is something else experiencing a “documentary,” and it ends when the “you” that you experience ends.

Commenter (CS): that’s a very good point but that’s still doesn’t explain when something decomposes and turns into nothing nothing can be made . before we were spam we came from nothing the atoms in the universe made us when we didn’t exist meaning over time after the bodies decomposed it will do the same possibly on a different planet where evolution is still new.

AA: There is no such thing as “nothing.” That’s a religious concept. Decomposition reduces physical materials into chemicals that are reintegrated into the environment. That’s a long way from “nothing.”

Molecular arrangements construct chemicals. Atomic arrangements build molecules. Quantum arrangements construct atoms.

Quantum bits of matter exist in flux between virtual and physical states. The virtual state exists in a theoretical state called “Quantum foam.” “Virtual particles” theorized to exist within “quantum foam” are described as potentialities because we can identify their physical state when manifested and extrapolate their “virtual existence” from behaviours we can observe.

The “state of quantum foam” exists “outside” the parameters we quantify as “spacetime.”

IOW. Reality “extends beyond” the physical universe.

Adding to that is the relatively recent discovery of microtubules in the human brain, which appear to interact with the universe on a quantum level.

This all suggests a connection between consciousness and whatever may exist outside the framework of our physical universe.

This implies human identity as a construct, not unlike a liquid, which takes the form of the mould into which it is poured.

IOW. “You,” as you experience “you,” exists only within the context of the mould you are poured into. Once that mould has deteriorated, there can be no more “you.”