This post is a response to a question posed in its complete format: “To which extent do novels, or manga, conveying deep idea, or talking about social issues, relate to them given global awards, or high global popularity, to which extent does this depend on how smart the creator is, why only few reach to this level?”

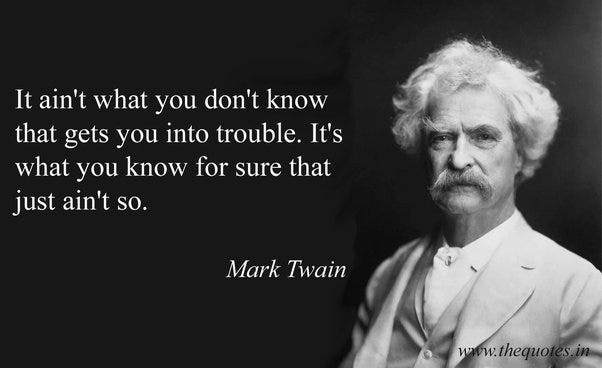

Popularity and recognition are primarily not determined by intelligence, creativity, or any value generally associated with degrees of quality, skill, or craftsmanship but by timing and resonance.

The kind of popularity attributed to intelligence and creativity is recognized only through endurance throughout the ages. It is the rarest form of popularity that remains consistently in the shadow of most other forms of popularity. It does receive the occasional boost because it can garner enough of a niche following to emerge on the populist stage for a time. Still, it then retreats to becoming a niche once again.

A book like “Fifty Shades of Grey” was a literary mess on every level, from the writing to the butchered subject matter to the horrid values it sensationalized.

It was a massive success because it appealed to a repressed and widespread imagination responding to an increasingly darkening reality by retreating into dark fantasies that most would not have the courage to explore in real life.

I’m certainly not claiming that I would or have the courage or the slightest interest in exploring this area of the human condition for myself. Still, I am at least aware enough of the dynamics to understand how the story itself represents more of an expression of a mind suffering from Stockholm Syndrome indulging in titillation rather than providing realistic insights into the dynamic it attempts to portray. It’s more of a study of mental health in society than a literary masterpiece.

This leads me to my point that, as a people, we have been enduring a staggering decrease in the quality of our lives over the last several decades, shocking most of us. A piece of schlock like this validates feelings shared by a large audience and titillates the imagination through sensationalized imagery.

It became popular, not because of any enduring qualities but because it fulfilled a need for an outlet.

“The Secret” is another example of appealing to repressed sentiment, but instead of validating the repressive darkness people have been suffering through, it capitalized on a need to restore hope.

Ultimately, both literary productions created more harm than good in the same way that trolls undermine the social contract.

Once materials like these run their course, they begin to resemble porn in that a temporary titillation is an insufficient mitigation for addressing underlying causes, and like cocaine, once it’s run its course through one’s body, one is left feeling drained and hungry for more of that emotion that gave them a temporary boost in life.

There is, sadly, no real cure to this phenomenon of populism beyond two different strategies. The first strategy is the sanest, but it is also the most long-term and invisible strategy for addressing this need to bottom feed while racing toward an ever-receding bottom. It’s a strategy that will make many eyes roll once I write it as a one-word summary: education.

Education is the “magic pill” that will mitigate most of humanity’s ills — at least, it will once we address the economic roots of humanity’s ills.

It won’t ever be a cure because there is no final state to education. There is no finishing an education. Only lifelong learning exists for our species if we wish to survive anywhere near as long as the dinosaurs did.

The alternative to education is our current self-destructive trajectory, which risks the end of human civilization and, quite possibly, our species if our rock bottom is deep enough.

The alternative track to education we are on is to continue our descent into worshipping the superficially constructed Holy Grail of attention for the sake of attention. We will continue to behave like addicts drawn toward the chaos of feeding an insatiable hunger until we consume all of what we value through superficial titillations that temporarily distract us from an otherwise horrifying existence.

Surviving the nightmare ahead of us means our future progeny will have slim pickings to choose from as representations of the best human potential to pick out from the forgettable detritus of populism. The future will be as we experience it today when looking back on history and forgetting how Leonardo DaVinci had many contemporaries competing for the same artisanal benefits he remains remembered for.

We don’t remember the easily forgotten mass, but we do remember the outliers, and that’s the broad lesson of history.

If we exist as a species and civilization in another two hundred years, no one will know who or what a Kardashian is. They will note, however, how rampant superficiality characterizes this primitive and barbaric state in which we live.

No one will remember any of the Harry Potter books or the trans-hating hypocrite who fraudulently represented hope within her discardable stories. They will, however, continue to be influenced by Tolkien.

No one will remember much of anything notable about the products of this era beyond the horrid worship of excess.

Not one talking head from Fox will be given a nod of acknowledgement for their contributions to society. Rupert Murdoch might earn a passing reference as a key player in corrupting human civilization. Even he will be regarded as a side note contributing to corruption. At the same time, his success at making it so widespread will be considered a global failure in ethics that permitted monstrosities like centibillionaires to exist.

Donald Trump will be remembered as this century’s Hitler, no matter how many may find that offensive today. It’s just where we are as a species, and history has given us enough hindsight information to make such predictions with great confidence.

Those who may be offended by this prediction would do well to consider how that’s an optimistic outcome to the trajectory we are on right now because if he succeeds in achieving the maximum potential of his efforts, then we may not have much left of humanity to be capable of studying the history we make today in any way resembling our current capacity for exploring our history from yesterday.

Suppose we don’t rein in society’s current excesses of distorted power. In that case, we will be lucky to exist in any state resembling anything other than a primitive existence at the mercy of nature.