Why does morality exist independently of human opinion?

This post is a response to the question posted on Quora as written above.

Morality IS “human opinion.”

Many differences exist between opinions on morality and on practically everything else people have opinions on — which makes opinions on morality somewhat unique in how they are perceived.

People generally do not equate a moral opinion on murder, for example, with an opinion on a fashion accessory.

Part of the problem is that it is the cultivated opinions of religious folk to believe morality is an objectively established standard of conduct determined by an invisible authority. If the claim of objective jurisdiction to develop and institute a moral framework existed, morality would essentially be identical and unchanging over time. That’s not the case for anyone who has made even a tiny effort to understand people or human history.

The most significant problem with establishing a universal acceptance of a moral opinion is that no one ever receives direct confirmation from an unassailable authority governing judgment over any specific behaviour. Complicating matters further are the subjectively supported morals of believers who do not share a consistent moral framework — even though religious institutions do their best to homogenize morality among their flocks.

Institutions that once endorsed slavery and have moved on to repudiating it cannot, without justified criticisms, claim to receive their moral framework from an omniscient entity.

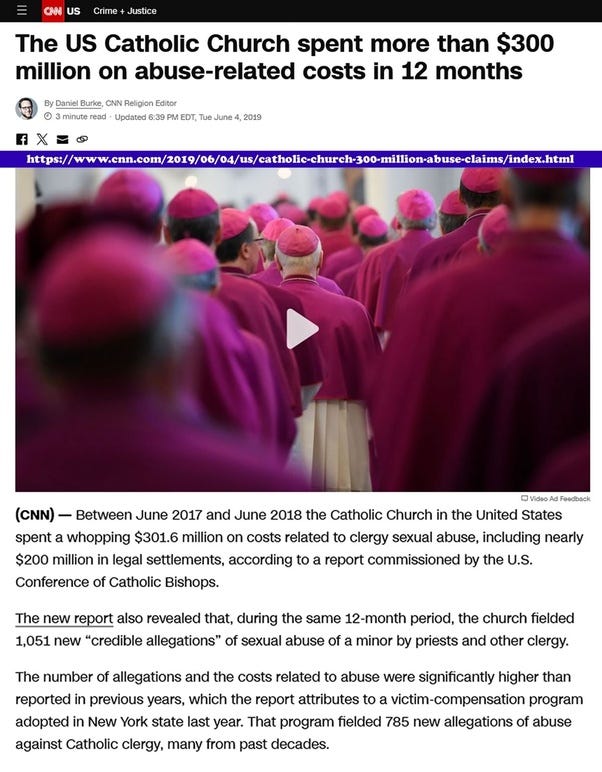

This and all the many other changes made to institutional policies regarding morality throughout the centuries have eroded religious claims of authority in moral matters. Making things worse for them has been allowing their credibility to be assaulted by many heinous scandals, such as the institutional endorsements for victimizing countless children through sexual predation and murder and the subsequent protections of institutional leaders guilty of immoral actions.

We, as a species and as a collection of diverse societies, all governed to some degree by the notion of morality, have undergone a tremendous number of and severity of degree in the assaults on our definitions for what constitutes morality that we are struggling to unify a fractured vision of the concept.

We can no longer trust our authorities, be they religious, political, industrial, or familial, which puts us in a quandary for resolving our moral differences as a species.

The upside is that we are turning inward to identify our internal sources of moral development.

Morality is most simply defined as an extension of empathy, but the issues it encompasses make that an oversimplification. At best, empathy is merely a compass guiding actions that many hope serve to achieve moral outcomes. Some will define morality within a self-serving context, while others consider self-sacrifice an embodiment of morality. Neither is necessary to achieve some form of widely acceptable definition of morality.

We can grasp a history of morality from academia, giving us context and perspective on what we have learned about morality. That approach leads us down deep and convoluted rabbit holes of (arguable) “subclassifications” like ethics, conscience, integrity, standards, and principles. At the same time, simple definitions escape a universal simplicity promised by our examples of failing leadership because morality is itself nuanced, multifaceted, and contextual.

We may never transcend subjectivity within the context of our interpretation of morality, but that’s a feature, not a bug.

Morality as an opinion forces us to share the diversity in our views, and that’s a superior form of morality to any authoritatively imposed dogma because we must each learn to develop our apprehensions of morality to learn how to better succeed in living together under a shared social contract to achieve a peaceful and prosperous co-existence.

We’ve seen enough artificially imposed forms of morality claiming objectivity as an unassailable standard for uniting people to know it’s a fraudulent approach to morality that invariably fails us as much as we fail to adhere to universally defined, generic, and external imperatives.

To accept morality as human opinion puts us in a position to define human character along a spectrum of universally acceptable, unacceptable, and inspiring behaviours that can adapt to an ever-changing landscape.

Morality may be more messy to manage as an opinion. Still, like the principle of a democracy, it’s the only form that can maintain coherence within the context of longevity.