This post is a response to a question posed in its complete format: “Are politics and marketing highly dependent upon, and structured around, the inability of the masses to think logically, act responsibly, and go beyond surface thought; especially go beyond surface thought?”

“All Publicity Works Upon Anxiety.”

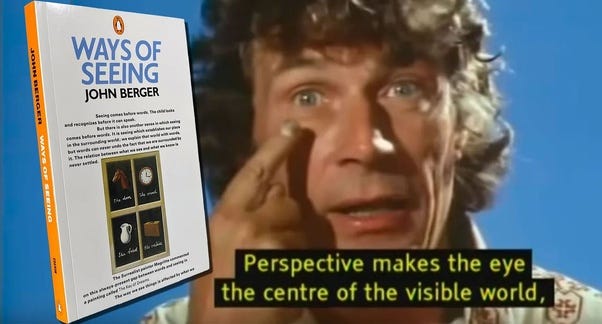

John Berger’s “Ways of Seeing” was an excellent introduction to my young mind as an art student in the early 1980s, helping me become more consciously aware of the then-daily bombardment of thousands of messages. It’s been decades, so I vaguely remember it, but I recall being repeatedly reminded of it over all this time. That suggests some “staying power” in my mind, with value over time. The book and/or the four-part documentary series created from it are both worthwhile experiences.

All four episodes have been combined into a single 2-hour YouTube presentation.

“We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves.”

The numerous concepts this short volume addresses introduced me to the layers of meaning in the images we encounter. The venue, the presenter’s intent, and the state of mind we bring to the viewing experience all coalesce into a unique perception we create for ourselves.

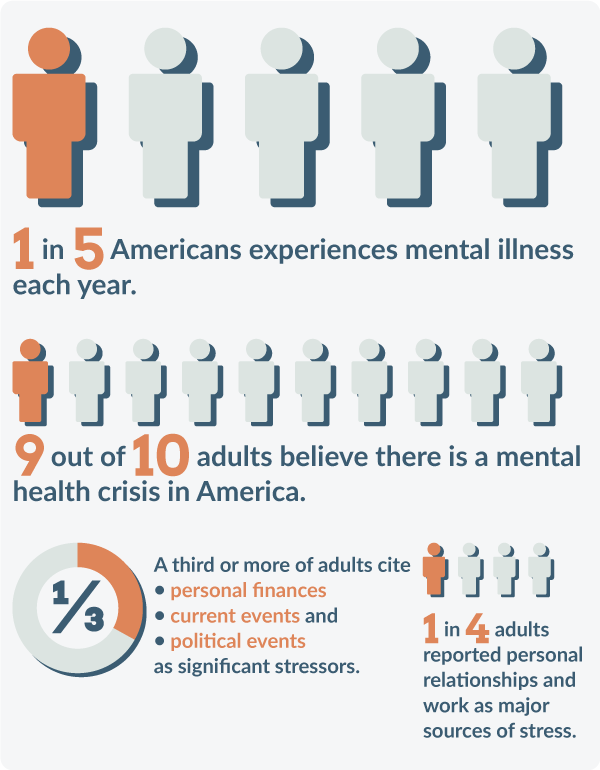

We are bombarded daily by thousands of images, according to the observations made in the early 1970s. I imagine the then-massive number I don’t quite recall at the moment (and am too lazy to scrub through the video to find it) has mushroomed by orders of magnitude since.

Marshal McLuhan challenged presumptions about media and its consumption.

We learned to think strategically about the messages we consumed.

His maxim, “The Medium is the Message,” gained him some notoriety among the media-savvy.

Then came “SEX” on a Ritz Cracker;

I’ve referred to a “we” requiring a definition. I think it was implied in “media-savvy” because it relates to awareness of what we are expected to believe and why it is essential to accept what is desired of us.

To be “media savvy” means being aware of the content of the ideas we consume and of how we choose which ideas to consume.

All Communication is Purposeful

We communicate not out of a compulsion to occupy idle time,

not even necessarily for social entertainment,

at least not when we go beyond the most superficial levels.

We communicate with one another because we must to survive.

Without communication, we would not be here today to examine our communication.

Who benefits most from what we believe?

It seems less about the people and more about benefiting those who have benefited most from a predatory system.

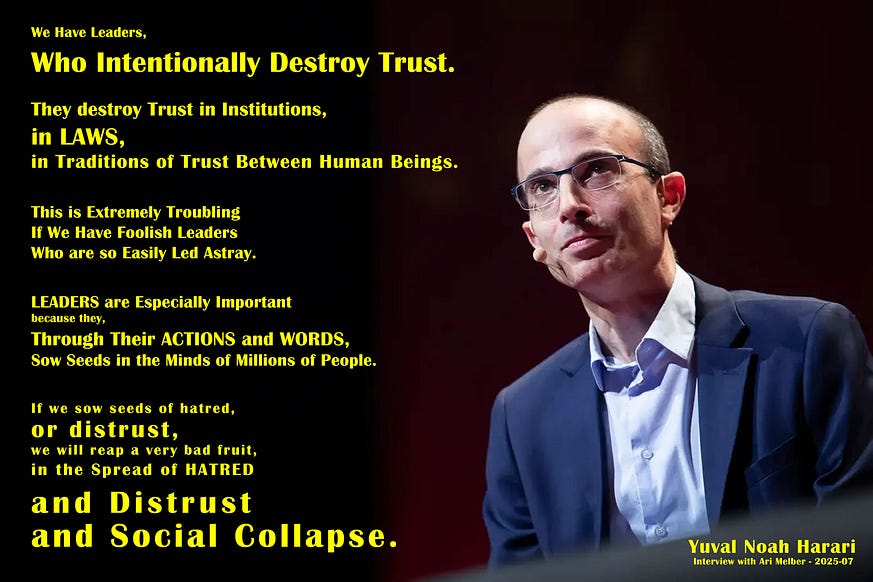

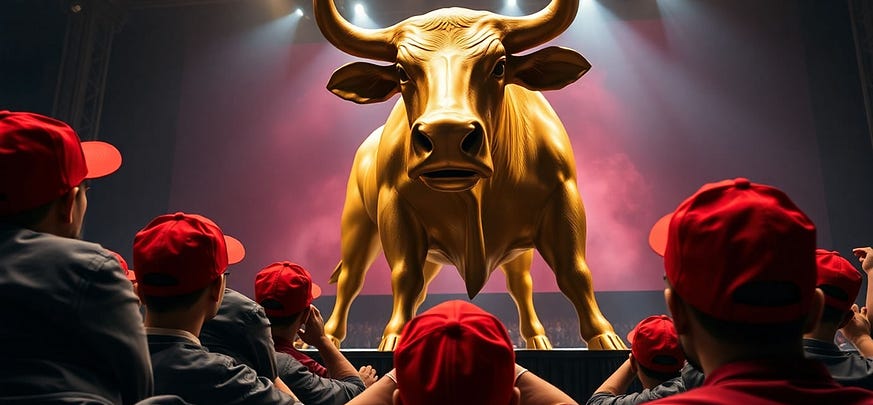

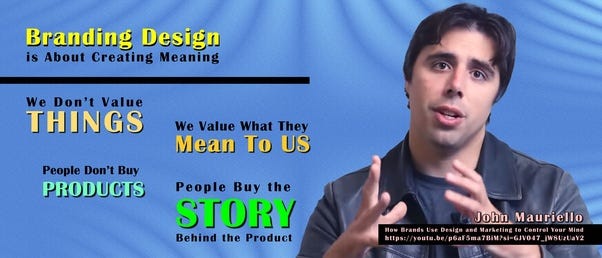

The above examples are from popular social discourse, about forty years ago and below is an example of current popular discourse:

(I refer to this example above as “popular” because it represents strategic messaging to serve a communication function of industry within the broader context of a culture structured around industry, economics, and consumption.)

The strategic manipulation of messaging is prevalent throughout society, in every domain, from interpersonal dynamics to international relations.

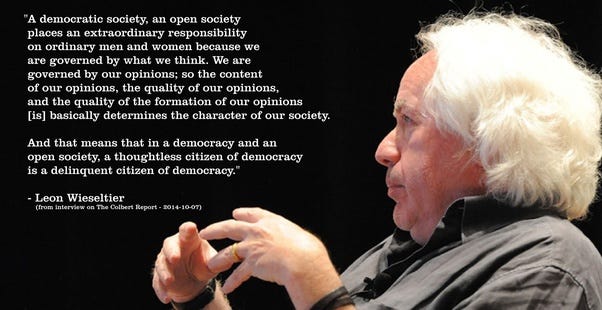

Whatever humans evolve into, some form of socially cohesive network of “shared perspectives” will perpetually question our experiences and compose new narratives to correct our collective perspectives.

Many of us do so with earnest and deep commitment to learning. Most will spare what time they can through highly structured days, allowing minimal opportunity for reflection.

We won’t stop thinking and talking about our experiences because we can’t. Willful ignorance may take centre stage from time to time, but it eventually gets the hook to exit left as it’s booed off the stage.

If the story doesn’t touch grass and meet reality, the people eventually figure out we’ve all been played for suckers by ever bigger games of power, and we find ourselves repeating history as ever-expanding dominions of power promise unity and deliver submission.

The barrage of imagery, sounds, videos, and merch-oriented stories has become increasingly overtly political. Factions grow around concepts and issues, not geography or physical commerce, but in the world of ideas, of how we think, how we see the world, and how the world looks back at each of us.

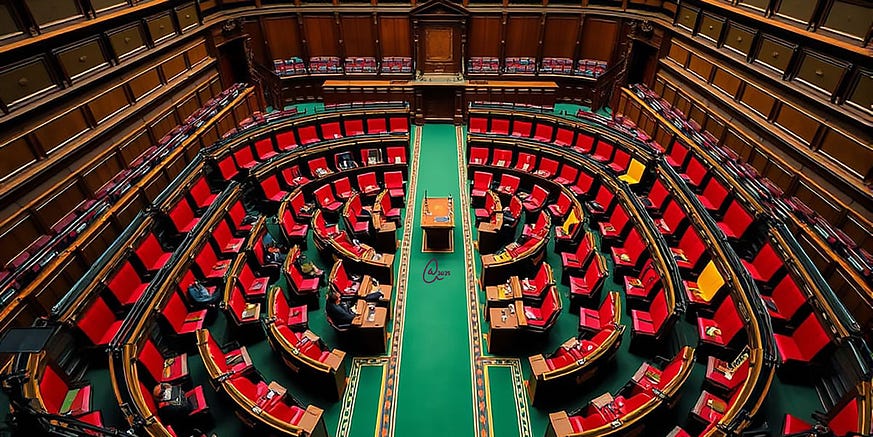

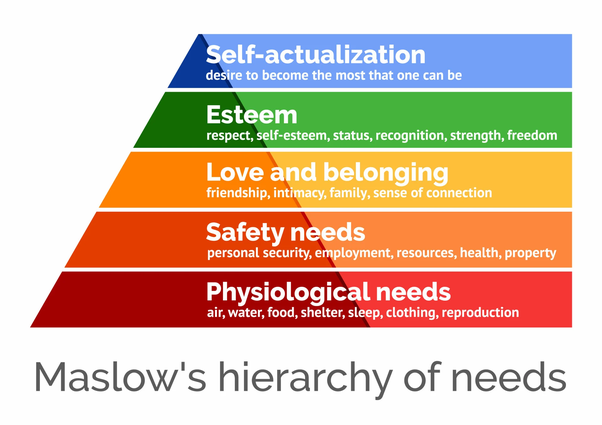

What do we want?

Certainly not chaos?

Chaos invariably leads people to one incontrovertible conclusion: for communication to succeed, there must be a relationship of trust. Without trust, there can only be chaos.

Choosing trust is a binary decision about life and what that means to each of us, from micro to macro scales, now encircling the globe.

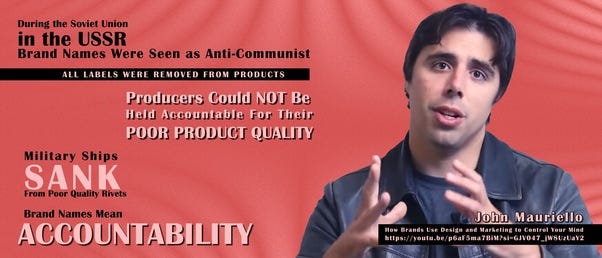

Trust Means Accountability:

One hundred years ago, our circles of trust were local and lifelong.

Today’s global reach with casual effort was unimaginable then.

Where we end up one hundred years from now is provocative to contemplate. Some form of examination of the information we consume will continue for as long as some similar form of abstract thinking persists.

How Aware Are We Today?

Or, how much awareness can our general public sustain without inviting chaos?

What do we reeeeeally know about what’s going on around us?

Well, that’s easy, chaos.

Changes are occurring everywhere while everyone competes for resources and integration into the general machinery of social production.

We know how power structures coalesce to construct universal narratives about the acceptable social order we are encouraged to support, while our own needs are increasingly neglected.

We know that some messages aim at social disruption, whereas others aim at social cohesion.

What we do as a society to facilitate cohesion after a half-century steady diet of failed promises.

I’m reasonably sure most of the public knows, or is becoming aware of, the apparent disarray in our politics. How dependent is this massive economic superstructure on our willing participation?

We must have leaders we can trust who will represent the needs of the many over the few who benefit most from a corrupted system gone askew.